Human data collection

Lesson Intro

You know about all sorts of “stuff.” How does that happen? How did you learn all those words and how did you know what they meant? How do you know how they connect, and where does all that information live? You didn’t write it down, did you?

The goals

-

Spend some time considering how you (as a human) organize information

Even if you don’t think about it, you know stuff. How might you map that out if you had to?

-

Experiment with how this information you know might be written.

You can call the information whatever you want. How does it look?

-

Think about how these concepts create shared language

Once we agree to call a collection of things by a name we can speed up communication, or destroy nations.

Dingle what?

Have you seen The Little Mermaid?

Some people call this little device a fork, and other people call it a Dinglehopper. But it’s the same thing no matter what you call it. However, you can totally use it as a comb and for many things besides eating spaghetti.

Repetition

I’m not sure why I believed everything my mom said when I was little. I guess she seemed trustworthy. My mom pointed to things on her face and said “Nose” and “Eyes.” I was a baby with an empty little brain. I heard other people say those words, and things seemed to check out. People agreed that those things could be referred to by those names.

As you hear words associated with objects or actions, you start to connect them. With repetition comes acceptance.

Brains are nuts

Watch this quick 2-minute video about brains from Harvard.

Power in words

Many people have said, “Girls have long hair, and boys have short hair,” but not everyone agrees with that statement.

When everyone in town calls you Mexican, even though you are American and your parents are actually from El Salvador, what does this mean?

If a majority agrees to something, it’s really powerful and not always great. I don’t mean to get too dark here, but these concepts describe how we see the world. Sometimes, they can overtake all logic. People kill over them. It’s easy to indoctrinate those willing to accept concepts as they are.

We don’t have an ideology to sell you. But if we did, it might be to keep asking questions and exploring and redefining these concepts as you continue to learn. There isn’t some magic ‘woke’ moment. We are constantly taking in new information and adding that to our mental models.

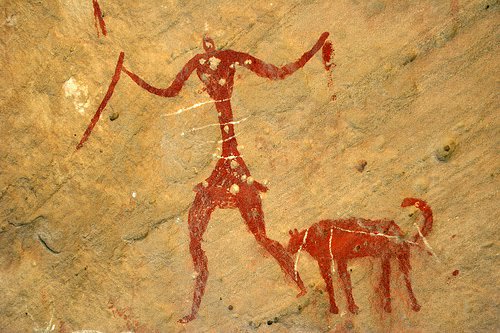

Early cave painting of a 'Dog' from Spain

If you can’t act out a dog in charades, and you can’t draw a picture, then how do you describe it?

Key

concept

Attribute

A quality, feature, or characteristic of something.

In our case, we are trying to describe the concept of a “dog” by outlining its attributes. Is it fast, sneaky, or furry? What is its color? Black, Gold, Brown? What pattern is its fur?

Dogs? Dogs.

It is easy to say, “Yeah, yeah, I get it.”

But take the time to really dig in and discover how these concepts are built in our minds. Let’s describe some things with pencils.

People seem to be obsessed with dogs. They like dogs so much that they are willing to pick up warm dog poop with a thin little plastic bag many times a day.

What is a “Dog”?

How can we describe it?

Well, they aren’t that big most of the time. I guess we could measure their height. You could use a ruler to measure. Feet and inches are concepts of measurement most of us (in the US) agree with. So, maybe your dog has a “height” attribute. The height would be a number. I’m not a mathematician, but a “number” is also a concept that we all agree on for some reason. They are useful. I’m going to say my dog is 24 inches tall. “Tall” is different than “wide” because we all agree that that is the case.

Despite what some people think, I don’t hate dogs. I had one once. His name was Bandit. So, “name” is an attribute. A name must be 1 level more specific than dog. It’s a name for this particular dog.

Dog (version 1)

- Name: Bandit

- Height: 24

Does anyone really think of dog height? (I don’t think so)

So far, we’ve used the concept of a “word” and “number” to help us describe the concept of a “Dog.” Maybe color, or running speed, or breed, or housebroken might help. Housebroken or “friendly” might be described with a true/false type concept.

I’m going to let you work out a much more complex version of the “dog” concept on your own and then go over it in tomorrow’s lesson.

Key

concept

Concept

An abstract idea / “an idea or mental picture of a group or class of objects formed by combining all their aspects.”

A concept isn’t unlike a mental-model. Other ideas to think of: A theory, Abstraction, an attempt to visualize a process.

Concepts are not always shared. They are usually a collection of attributes and experiences.

For example, “Fathers” are shown in movies as strong, providing, loving figures. The prevailing concept of fatherhood is that you should be a good Dad. There is a mess of expectations, experiences, emotions, scenes from Television, and family experiences. But what does that mean? And is it really the norm? I would argue that “bad dad” is probably the norm (I like my dad, but based on the people I’ve met in my life).

Is a dog just the cutest little thing you ever saw… OR is it that thing that bit you – and that you’ve been terrorized by your whole life? And it’s hard to describe feelings so, how do you convey that in simple attributes?

We are in charge

This whole “Dog” idea is made up in our mind.

Concepts are usually made up of other concepts. Even the idea of a concept is a concept. We could call it a ‘construct’ instead, or any number of words. It doesn’t matter. Our point in breaking it down is to reexamine what is happening behind the scenes in our brains. To communicate with each other, we need to share a set of concepts, and in that way, a language.

The computer doesn’t have a magical ability to organically categorize everything, group it, and make life-long associations. You have probably heard of machine learning, and that’s great, but it’s nothing like having hundreds of generations of DNA stuff that tells it not to eat the red berries. It’s not whatever we are.

When we tried to teach the machine, we had to find a way to share a language. To communicate, we need to share a set of concepts to give the computer directions. We’re not really THAT smart, so we just used our own language (for the most part).

“Numbers” and “Words” and maybe something like “nothing,” or “yes” and “no,” or “true” and “false” are the only ways we know how to describe things.

There are also these other things that the concept does. Like run or bark. Just like dingle hoppers and forks, it doesn’t really matter what we call them; it’s more important that we agree on what we call them. It would be really annoying to have all of the words changing every day.

Spend some time and experiment with this stuff. There are probably more concepts to describe things that I haven’t thought of in this lecture. What do you think?

I generally refer to these concepts as “things.” It’s easy. I’m pretty sure you do it all the time. So, I want you to take today and tomorrow to really think about all of the things you see and interact with. Are they Items? Animals? People? Songs? Sounds? Feelings? You tell us. Get weird.

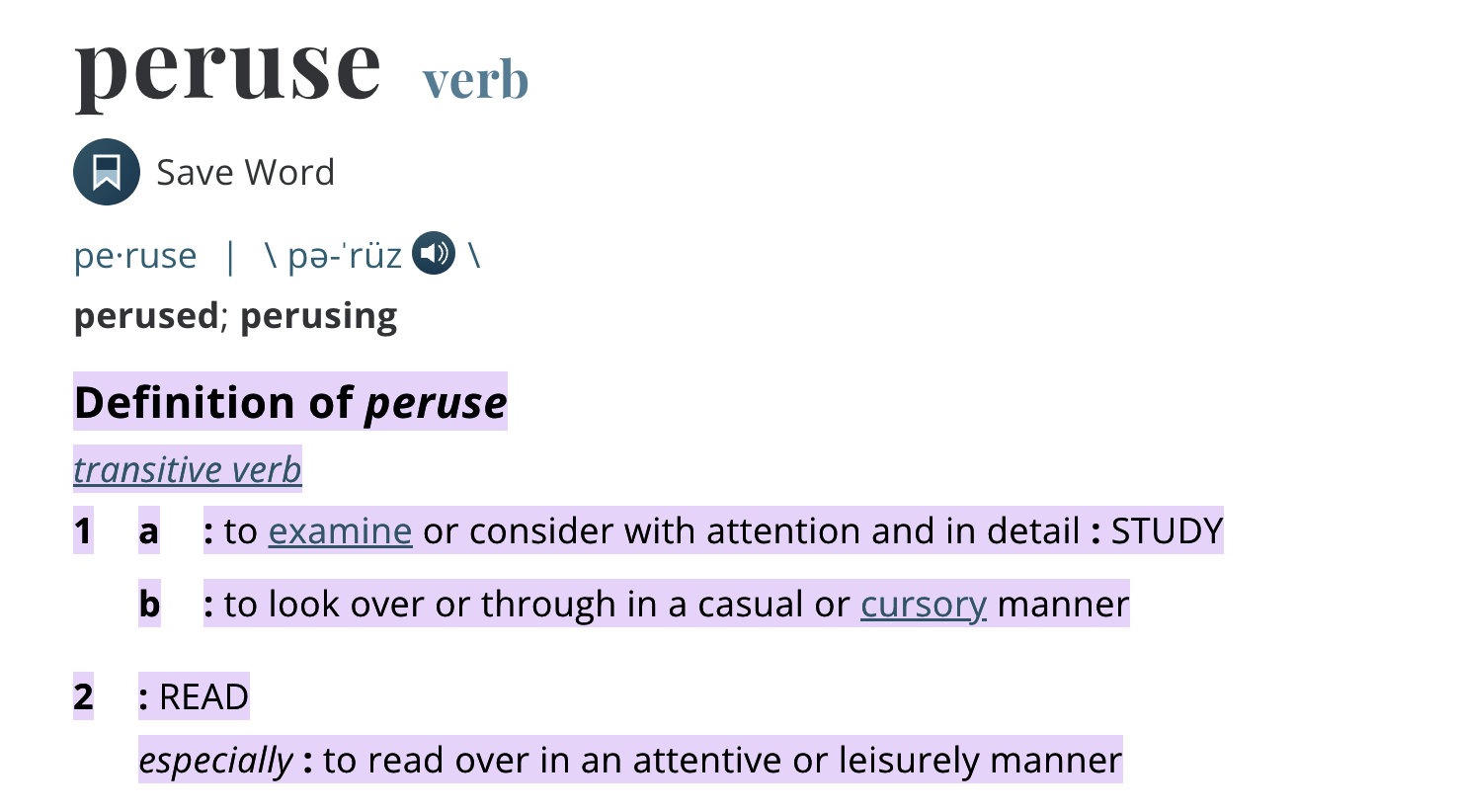

What?

So do you want me to just flip through it really quick? Or pore over it late into the night at the library for weeks?

In conclusion

Programming, Science, code, design, and data structures can all sound complex and intimidating. Sometimes, we just blur them out and assume that they are for other types of people. At the core, most of this stuff is pretty basic, but we haven’t been trained to see it that way yet. Try and let go of those feelings and just focus on how we’re already working with all of those things in our daily lives under the hood in our brains!

Computers were made by people, just like you.

Exercises

-

Do your first "standup"

You’ll probably take some time to read about it (which will take some time), but writing it up and posting it should only take a few minutes.

-

Tell us about some "things"

Get out some paper and pens and draw an outline of three or more concepts from your life. Try drawing it in a few different ways. Make sure the concepts are complex enough to have ten or more attributes.

-

Share your findings with the team

Take pictures of your conceptual drawings and share them.

Lesson checklist

These are just prompts to help you contextualize today’s subjects.

-

You spent some time thinking about how little bits of information make up bigger bits of information, and those bigger bits of information make up even bigger “things,” and so on

-

You’ve spent enough time to push that into places that made you think a bit more about how strange that is.

-

You’ve tried to see it from the perspective of someone who is charged with mapping out data to share spoken languages or possibly even how to share this information with a computer.

Deliverables

This “deliverables” section is a new module that some students wanted to make. But once they started building their own projects, they promptly forgot about it! It’s not styled. We were still deciding on a consistent voice for how these are written. What do you think? Let’s have this group formally decide how the deliverables or checklists for the lesson should work.